In The Weird and the Eerie, critic Mark Fisher explores the sense of something’s being simultaneously unsettling and fascinating. “Weird” and “eerie,” according to Fisher, are the feelings you get when, in World on a Wire, Stiller realizes that what he thought was the “real world” is actually a simulation controlled by a “realer” world; or when, in Mulholland Drive, Rebekah Del Rio collapses in the middle of singing “Crying,” but we continue to hear her singing. Brian Eno’s Ambient 4: On Land, with its restless soundscape evoking the Suffolk of Eno’s childhood, is eerie; as is Picnic at Hanging Rock (both the novel and the movie), with its intimation of an “outside” that can only be accessed through delirium.

Here are some examples of interactive fiction that I would consider weird and/or eerie. (Note: I have also made this into a poll on IFDB, so please check there for community additions!)

The games are Shade, The Good People, and You are Standing at a Crossroads. Spoilers ensue.

The Weird: Shade (Andrew Plotkin, 2000)

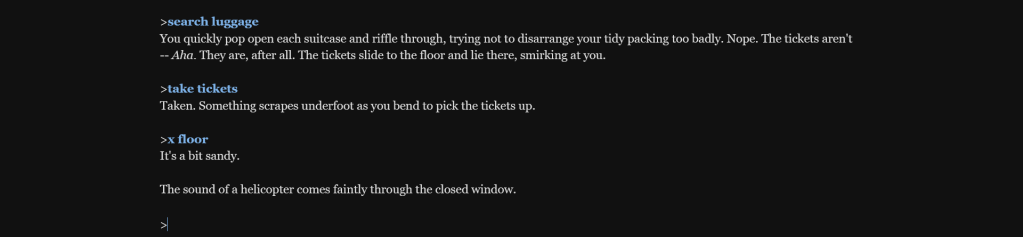

Itʻs early morning—still dark—on the day you are scheduled to fly to California for a Burning Man-like festival in Death Valley. The taxi will arrive at your apartment in a few hours, and you can’t find your plane tickets. The search for the plane tickets initiates a sequence of tasks that causes the very walls of your apartment–and along with them, your reality–to gradually disintegrate, enabling one world to infiltrate another. The game is in fact full of unstable “portals” (the mirror, the radio, the computer, the book, the window) and suggestions of other worlds and realities, beginning with the title itself, and its allusion to the underworld.

In this regard, Shade is very much in line with what Fisher characterizes as the weird: “Worlds may be entirely foreign to ours, both in terms of location and even in terms of the physical laws that govern them, without being weird. It is the irruption into this world of something from outside which is the marker of the weird” (20).

The Eerie: The Good People (Pseudavid, 2019)

Pseudavid’s The Good People, on the other hand, best embodies what Fisher categorizes as the eerie. Fisher distinguishes between the weird and the eerie as follows: “As we have seen, the weird is constituted by a presence – the presence of that which does not belong. In some cases of the weird (those with which Lovecraft was obsessed) the weird is marked by an exorbitant presence, a teeming which exceeds our capacity to represent it. The eerie, by contrast, is constituted by a failure of absence or a failure of presence. The sensation of the eerie occurs either when there is something present where there should be nothing, or there is nothing present when there should be something” (61).

The Good People takes place in the ruins of a small village (not even big enough for two churches) that was flooded by a reservoir many years ago, forcing the protagonist’s ancestors to move. Climate change has since caused the reservoir to dry up, revealing a parched landscape in which people, wildlife, and even clouds are eerily absent.

In Fisher’s conception of the eerie, the question of agency is central: eerie absences and presences suggest invisible forces (of a supernatural OR temporal nature–Fisher identifies capitalism as one such force) that leave their traces on our world. In The Good People, it is climate change and capitalism (“All our generation is always selling”) that function as “eerie” agents shaping every condition of the charactersʻ lives.

The Weird: You are Standing at a Crossroads (Astrid Dalmady, 2014)

In You are Standing at a Crossroads, you wake up at the eponymous crossroads with dirt on your face and no recollection of what happened before. Four roads lead in the cardinal directions. You explore the four scenes, which shift in strange ways each time you revisit them. Yet somehow, you always return to the crossroads.

In the crossroad world, there are indications of life–the cries of animals, hot and humid air, a viper spine, a feather, candy wrappers and empty soda cans–but no living creatures besides plants. Beyond the crossroads is only “endless, unceasing grey.” The game suggests an outside (“Where are you, and how can you get out?”), and toward the end of the game “a grey train” pulls up to the crossroads–which has now become a train station. You board, hoping to be delivered beyond the grey horizon, but in the game’s last sickening moment, you wake up from a nap and find yourself back at the crossroads.

You are Standing at a Crossroads embodies some of the “strange loops” and “ontological weirdness” that Fisher explores in his chapter on Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s World on a Wire and Philip K. Dick’s Time Out of Joint. In both works, Fisher says, we experience “…an abyssal falling away of any sense that there is a ‘fundamental’ level which could operate as a foundation or touchstone, securing and authenticating what is ultimately real” (48).

You must be logged in to post a comment.